The weather headlines this summer have been about heat,

heat, and more heat. But it hasn’t been hot everywhere, and one of the places

where it hasn’t been particularly hot is where I live. Which is not to say that

summer weather has been uneventful.

We often found ourselves on the northern periphery of the

heat bubble that affected the southern tier of states during most of the summer.

At times the mixing of hot and moist air with cooler, drier air resulted in

outbreaks of severe thunderstorms along portions of the periphery. We’ve

experienced four of them so far, on June 1, July 1, July 14, and July 29. Each

time we lost electrical service as a result of downed electrical lines. Living

in an area with overhead lines and many large old trees, any episode of high

winds brings down limbs and sometimes entire trees onto the lines, cutting off

electrical service for some people. We’ve become accustomed to losing

electrical service during severe thunderstorms. Usually it remain off for a few

hours, and we have a routine established for such short-term outages. But the

damages in our area from the July 14th storm were so severe that it

took our electrical utility 47 hours to restore our electrical service. We were

without electricity from about 7:30pm on the 14th to about 6:30pm on

the 16th. The photo above shows one reason for our loss of electricity: two houses up the street to the west, a trunk of a silver maple tree fell on the overhead electrical lines and across the full width of our narrow, two lane, low traffic street.

The last time our electricity had been out for so long was

in 2006, following two severe thunderstorms about 36 hours apart. We had no

electricity for 6 days after the second storm. What we learned then had already

been incorporated into our power-out routine. To make things easier, our

nearest grocery store and some of the local gas stations installed generators

as a result of the 2006 storms, so we could readily obtain ice and groceries

after this storm. But I hadn’t fully accounted for another change since 2006,

which came to the forefront during this 47 hour outage.

In this post I’ll discuss how we fared during the recent

outage and what we learned for the next one – because there will be a next one,

and another, and another. That’s what decline looks like. I hope you can learn

something from our experience that helps you the next time an electrical outage

happens to you.

Air conditioning

Most of the people we told about our 47 hour outage

expressed the most discomfort about not having air conditioning during that

time. For us, that was the least of our concerns.

Granted, the few days before and including the day of the

storm featured some of the hottest and most humid weather we’ve had this

summer. We had our air conditioning on, set at 80F as we prefer, when the storm

hit. Along with the high winds, we received about 2.3 inches of rain.

Rain cools the air. Immediately following the thunderstorm,

the temperature dropped from the upper 80sF to the low 70sF. We responded by

opening the windows to let in the cooler air. It was more humid air than

the air in the house, but by living our lives in the house, we

raise the humidity just by breathing. With all of the windows open wide, we

cooled the house enough to sleep comfortably that night.

As we always do in the summer to minimize air conditioner

usage, we left the windows open the next two mornings until the temperature rose

outside to above the interior temperature, then closed them. In the evenings,

after the outside temperature dropped below the inside temperature, we opened

the windows again. Two other improvements to the house that we’ve made over the

years, sealing against air leaks and adding insulation in 2005 and new windows

last year, combined with the strategic opening and closing of the windows, kept

the temperature inside the house at 76 to 78F. It helped that the weather

cooled off as well, with highs of 89F and 92F on the 15th and the 16th.

Even if we hadn’t lost electricity, we would not have run the air conditioner

after the rain cooled the air, nor did we turn it back on after our electrical

service was restored. We spent most of the two days of the outage, as we do

during the warmer months of the year, on the roomy and breezy back porch rather

than in the house.

Lighting

We have collected quite a few sources of off the grid

lighting over the years, which we employed during the hour or so we were awake

in the evenings after the sun went down. Among these are two oil lamps that sit

on the low shelf separating the two largest rooms in the house; multiple

flashlights, including the one on a headband that I use for reading and seeing

my way around the house during outages; and a candle for light in the bathroom.

We have two battery-powered lanterns as well (we keep their batteries sitting

next to them so they don’t corrode and install the batteries only when we put

them to use), but with it being summer the days were long enough that we didn’t

need to employ them. We ate meals on the back porch instead of in the kitchen

as we usually do, because it was brighter on the porch.

Refrigeration

With scattered severe thunderstorms predicted for the

evening of the 14th, we chose to eat dinner earlier than usual so

that any leftovers would be in the refrigerator and cooling down if not already

cooled before a storm hit. After the storm, we implemented our

don’t-open-the-fridge rule to keep the contents cool enough that we wouldn’t

need to worry about them until the next morning.

I know that “experts” claim that the food in

refrigerators only stays cool enough for safety for 4 hours. Let me unpack what

I think are the factors that go into that advice.

First, it seems likely that the “experts” expect someone in

the house to open the refrigerator door at least once, if not more than once,

during that four hours. Opening the door lets some of the cold air out,

replacing it with room-temperature air. If no one opens the door, this exchange

of air takes place much more slowly, allowing the contents to stay safely cool

for a longer period, especially if the contents are all at refrigerator

temperature at the time the electricity goes out. That’s why we keep aware of

our local weather and the local NWS weather radar when severe weather is

predicted, and why we always eat any meal that we would normally eat around the

time of expected severe weather well before that time, so that we can keep the

refrigerator closed for several hours in case of an electrical outage.

Second, the “experts” most likely have lawyers advising

them. Lawyers are paid to be risk-averse and advise their clients accordingly.

I am NOT advising you to do what we do! We are willing to take some risks as

long as careful thought suggests that for us the risk is minimal. All readers

need to assess their own situations carefully and act accordingly.

The next morning, the electricity was still off. I checked

for news about the outage on the emergency radio because we don’t have internet

service when the electricity is out and neither Mike nor I have a data plan on

our cell phones (more on this in the communications section). The brief local

news report on the major local FM station didn’t mention the outage, suggesting

it was restricted to a relatively small area, but a look at our street showed

that nothing had changed since the night before. We began to suspect that we

might not have electricity for at least several more hours and that it was time

to get some ice and transfer the contents of the fridge to coolers. After visiting a local donut store for donuts and hot coffee and tea, allowing us to add some charge to

our cell phones (see the communications section), we bought ice and

transferred all the food that needed continued cooling into coolers with ice.

We left cheese, butter, and the garden vegetables in the fridge since they

didn’t require being cooled to stay safe. We transferred the food in the

freezer compartment to the chest freezer along with another bag of ice to keep the food in

it from thawing. Having done this, we could eat from the foods in the cooler as well

as the various canned foods and the pretzels and crackers that we keep for

eating during shorter-term outages when we aren’t opening the refrigerator.

On the 16th, when electrical service still hadn’t

been restored, we emptied the bag of ice in the chest freezer into the coolers

and bought two more bags of ice, which we put in the freezer unopened to

keep it cool. If the electricity hadn’t been restored by the morning of the 17th,

we would have considered getting dry ice for the freezer, but we hoped that

wouldn’t be necessary. We would have then used the ice in the freezer for the

coolers. After the electricity came on in the evening of the 16th,

the bags of ice in the freezer became available for future electrical outages –

and we used one of them during the outage on the 29th, because the

electricity had already been out for about 5 hours before we went to bed. The

second bag is still in the chest freezer, ready for whenever we next need ice.

Cooking

We have an electric stove so we couldn’t use it during the

outage, but we also have several means to cook food without electricity. Had

the weather been sunny I would have employed the sun oven to heat water for tea

and coffee and to heat foods from the cooler as desired, but conditions were

too cloudy for its use. We could have heated water or leftovers or cooked on

the propane grill or the charcoal grill, but as it turned out, we didn’t do

this. Instead, we got tea and coffee from the donut store and a local gas

station, ate out the evening of the 15th, and got a rotisserie

chicken the late afternoon of the 16th from the local grocery store

because I wanted to eat hot rather than cold food for dinner. Otherwise we ate leftovers

out of the coolers.

Next time, we’ll do more to

employ non-electric sources of heat for cooking, as I am not fond of a

continued diet of cold foods, and meals out are increasingly expensive.

Communications

This was our biggest challenge during this outage.

In 2006, while we lost internet service once the battery

backup lost charge, we retained landline service because the phone was hard-wired

into the phone network. Neither of us had cell phones then. Not having internet

service wasn’t a big issue, as our service was slow and used primarily for

email, which we could check on the computers at the library.

For several years our battery backup module for internet

service has been inoperable, probably due to failure of the battery inside. We knew where we could take our unit to get the battery

replaced. We just hadn’t done it and accepted the loss of internet during

electrical outages, knowing that if we really want or need service, we can take

our computers to the library to read and respond to email and to read some of

the websites we frequent. I’m a reader rather than a video watcher and I always

have multiple projects in progress that don’t depend on the internet, so I’m

never bored. Mike likes to watch short videos on the net but he likes to read as well, and

we play our own music rather than listen to others play music. In short, we

enjoy internet but don’t require it to make our lives bearable, and we have

more than enough to do when it isn’t available.

On the other hand, since most of our electrical outages are

for less than 8 hours, and because our electrical utility forces us to stay

abreast with information on outages through its website, it would be good to

have the battery backup module working again. I’ll take our old module in for

battery replacement soon.

We still have the landline phone but now it’s connected to

the fiberoptic system and we supply the electricity to run it, so it is

inoperative during electrical outages. Our cell phones work during outages – as

long as they are charged. Our standard procedure when severe weather threatens

is to charge up our cell phones well before severe weather hits. But I neglected to charge my phone before this storm. That was a mistake, as I had less than two days’

worth of charge on my phone when the electricity went out.

Mike wasn’t as affected by the lack of electricity for

charging his phone, because he could take advantage of one of our alternative

means to charge the phones, via an adapter to charge it from the car battery.

He had two events at the Zen center he belongs to, and it’s far enough from us

that he could get a good charge on his phone by driving to and from the Zen

center. However, the only riding in the car that I did was on much shorter

drives that did little to charge my phone. My only alternative was to limit

phone time. Even then, my phone dropped to near zero charge before the

electricity came back on.

Our other alternative means to charge the phone is from our

emergency radio, which has three different ways to power its internal

rechargeable batteries: solar cells, a hand-cranking system, and an AC adapter

to charge it from our electrical service. It has an adapter with a USB port on

one end and a jack into the radio on the other for charging cell phones. It

also accepts three AA batteries, so it doesn’t need to use the rechargeable batteries for radio service. We got the radio in 2016, when we were

still relying more on the landline phone than our cell phones, primarily for

its function as a receiver of FM, AM, and weather broadcasts when we don’t have

electricity. While I knew it could be used to charge our cell phones, I hadn’t

tried to do so.

When I realized that my cell phone didn’t have enough reserve

charge to remain usable through the expected length of this outage, I remembered

that in theory I could charge it from the radio. But I didn’t remember where I

had stored the adapter for that purpose, and I began to fear I’d lost it. Even if I had found it, the rechargeable batteries would not have had enough charge to add much charge to my cell phone.

Earlier this month, I consulted the website for the radio’s

manufacturer and discovered, much to my relief, that the cell phone charging adapter was offered

for sale as a replacement part. I promptly ordered one. Then, before it

arrived, I got it in mind to look again for the adapter and discovered it in the tray

of a desk drawer, hidden under a pile of rubber bands. So now we have two

adapters. In the meantime, I found the manual for the radio and read it more

closely, learning that the AC adapter would charge the rechargeable batteries

more quickly than either the solar cells or the hand crank. The AC adapter

doesn’t come with the radio but it can be purchased from the same website.

After checking our collection of spare AC adapters and not finding a suitable

version, I ordered the AC adapter from the website. It’s arrived and I’ve

charged the internal battery with it. I also found a small cloth bag to keep

the cell phone adapters and the AC adapter in and put the bag next to the radio,

so we can find them the next time we want them. When the cell phone next needs

charging, I’ll try charging it from the radio.

The other issue I may address is the lack of a data plan on

both of our cell phones. Mike has an Android smartphone but doesn’t have a data

plan with it, so he can only talk or text during electrical outages. I have a

flip phone that doesn’t have a data plan option, so I can also only talk or

text in that situation. I’m considering upgrading to the smartphone and data

plan that my provider offers, because it would be helpful to have the ability

to access our electrical utility’s website during electrical outages.

I hope you all enjoy the rest of summer (or winter if you

are reading from the southern hemisphere)! I expect the next post to be a quick

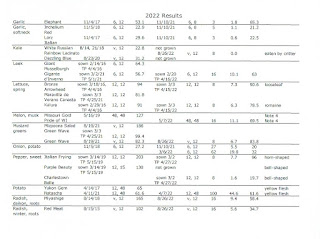

update on this year’s garden.